God wants Ethiopians to prosper

The prime minister and many of his closest allies follow a fast-growing strain of Christianity

“THE REASON why we are

poor is inside us,” cries Nigusie Roba, his face sweating with emotion.

“It is not the fault of God.” The pastor’s youthful congregants rise,

palms open wide. Nigusie’s voice grows louder: “Tonight you will go home

anointed by God.” In the far corner a young woman drops to the floor,

her body writhing as she screams.

Preachers like Nigusie—sharply dressed, charismatic, and renowned for

exorcising demons from the bodies of the faithful—represent a strain of

Christianity not widely associated with traditionally Orthodox Ethiopia.

For centuries national identity was entwined with the conservative

ritual and hierarchy of the continent’s oldest church. But “Pentes”, as

both Pentecostals and more staid Protestants are known in Ethiopia, are

on the march.

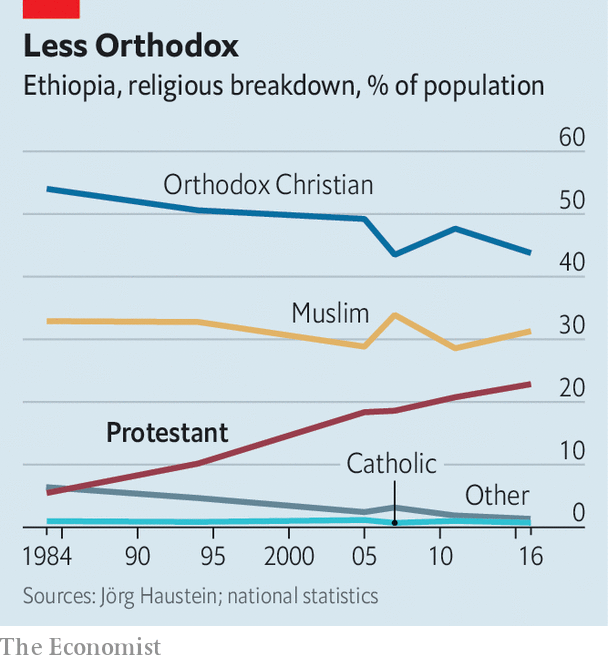

In the 1960s Pentes were less than 1% of the national population. Today they may be as much as a quarter, packed into cities and among the fast-growing rural populations in the south and west. Most of this growth has come at the expense of the Orthodox Church (see chart).

Before the EPRDF introduced freedom of religion in 1995 the Pentes were fiercely persecuted by the Orthodox establishment and its allies in government. When Abiy’s church, Full Gospel Believers, tried to register in 1967, its application was rejected by the then emperor, Haile Selassie. Arrests and beatings followed, worsening under the communist regime known as the Derg. In 1979 some church members were publicly flogged as punishment for not chanting socialist slogans. Popular hostility was rife, too. When one of Nigusie’s children died in infancy, some of his neighbours in southern Ethiopia dug up the grave and hung the corpse on a post as a warning to others.

Even during those dark times Pentecostalism won converts. In much of Oromia it has also grown with the rise of Oromo nationalism, in part because sermons are conducted in the local language, Afan Oromo, rather than Ge’ez, the ancient language of Orthodox liturgy (akin to Latin for Catholics). Most of the founders of the Oromo Liberation Front, a secessionist rebel group, were Pentes.

Today the faith’s modern image explains its rise better than politics. In the Assemblies of God chapel upbeat pop music welcomes Nigusie on stage. A new wave of charismatic pastors known as “Prophets” attract huge crowds by telling followers that God will make them prosper. Suraphel Demissie, who grew up as an orphan, has a 24-hour satellite television channel, tens of millions of YouTube views, a large office in Addis Ababa and an international following. “The beguiling feature of Pentecostalism ...[is] the idea that nothing is impossible,” says Andrew DeCort of the Ethiopian Graduate School of Theology.

Ideas like these can be revolutionary. Dena Freeman, an anthropologist, found how a large majority of people in a rural district in Ethiopia’s southern highlands converted to Pentecostalism in the early 2000s. The individualism taught by the religion encouraged a boom in businesses, in part because it freed people from traditional obligations to share their wealth.

The former guerrillas who used to run the EPRDFdrew a sharp line between religion and state when they came to power in 1991. But religion seems slowly to be returning to the public sphere. Although there are few signs that Abiy favours Pentes at the expense of other faiths, religion seems to have shaped his politics. Many of his sermon-like speeches about love and forgiveness invoke God. Moreover, many of his followers see him as being on a divine mission. He seems to agree, having said that as a child his mother prophesied his rise.

(Source: The Economist)